When you receive the title of “Toy of the Century,” success is guaranteed, right? LEGO seemed to think so. After all, whether you grew up in the 60s or consider yourself a 90s kid, one toy connecting each generation to the next is LEGO. The building block toy offered children all over the world the chance to show their creativity and build something unique.

As promising as that all sounds, LEGO found out firsthand how quickly everything can come crashing down. After decades of growth, the company was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. As the world now knows, LEGO was able to make a comeback, but that was far from certain at the time. To do so, they needed to rebuild brick by brick.

An analysis of their comeback shows how effective LEGO’s strategy was. The company made a triumphant return to what made them so successful in the first place. New leadership helped LEGO overcome its challenges by embracing the business’s roots and reconnecting with customers. The company also explored new frontiers that would help them get back on their feet. It was in creativity that LEGO was able to make things click again.

LEGO History

Like most businesses, the history of LEGO starts with humble beginnings. A man named Ole Kirk Kristiansen founded The LEGO Group in 1932. The word LEGO is a combination of two Danish words, “leg” and “godt,” which mean “play well” in English. As you might expect, Kristiansen’s company specialized in toys. Kristiansen wrote that the decision to create toys wasn’t an easy one at the time, explaining:

“It wasn’t until the day I told myself, ‘You’ll either have to drop your old craft or put toys out of your head,’ that I began to see the long‑term consequences. And the decision turned out to be the right one.”

Early on, the company built wooden toys, and it wouldn’t be until 1949 that the business developed a product called “Automatic Binding Bricks” made from plastic. These bricks would later receive the name LEGO bricks in 1953, setting the company up for what would be their signature product.

LEGO is also known for their LEGO sets, though it’s harder to pinpoint what the first LEGO set was. Most experts seem to agree that the first LEGO set as we know it would be the LEGO System Garage with Automatic Door, released in 1955. By 1957, Godtfred Kirk Christiansen would take over much of the management of the company from his father. The new leader saw the potential of LEGO bricks and the importance of quality. “[W]e must make better bricks from even better material on even better machinery,” he said. “We must get the best people for our company.”

LEGO Sets a Course for the Future

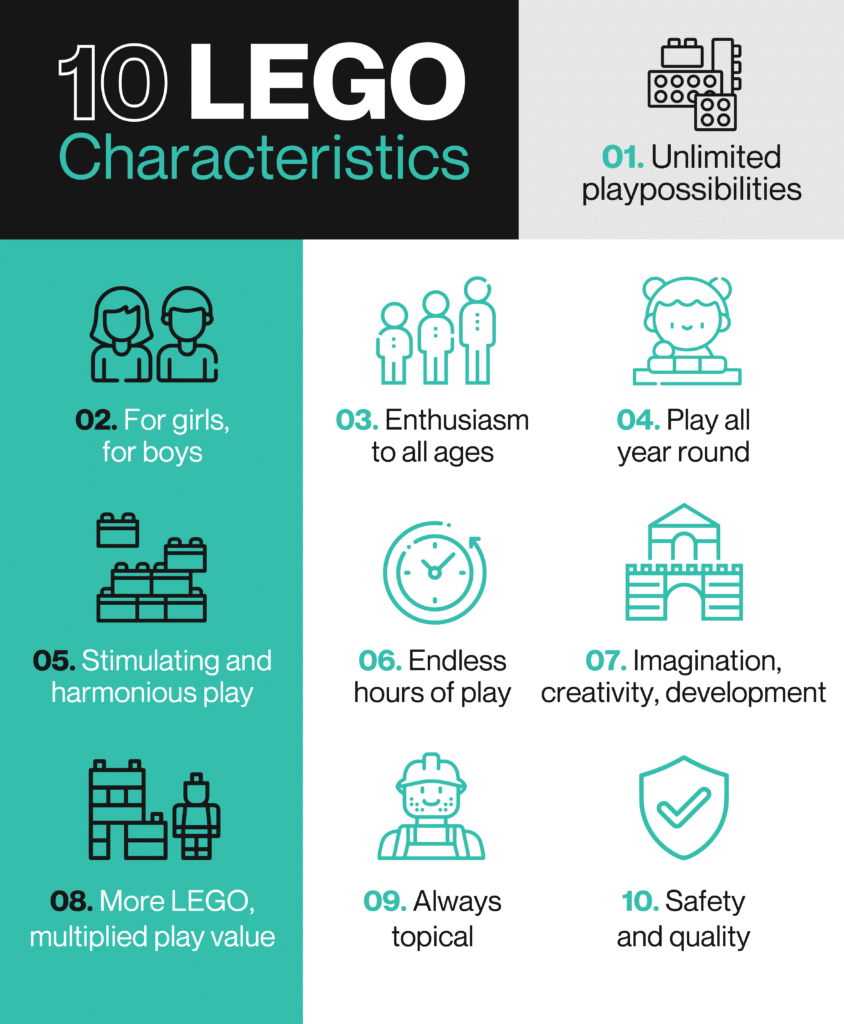

One of the turning points for LEGO occurred in 1960 when a fire destroyed the warehouse where the company stored its wooden toys. Company leaders made the decision to finally discontinue making wooden products and focus on the lucrative plastic LEGO bricks that had become a success. Over the next decade, LEGO would expand, with the first bricks ever manufactured in the U.S. in 1961. During a conference in 1963, Godtfred announced 10 LEGO characteristics that would shape the vision of the company and serve as guidelines for its products.

Over the years, LEGO would continue to add to its impressive catalog. In 1979, company leadership would change hands once again, though it would remain in the family under Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, the new CEO. Of note is that Kjeld was the first person within his family to actually hold a business degree.

During the 70s, 80s, and 90s, more themed LEGO sets would launch to the public. These themes included space, medieval, and pirates. The success of LEGO would continue until perhaps one of the most impressive rewards of all in 2000, when the British Association of Toy Retailers named LEGO the Toy of the Century. LEGO beat out such iconic competitors as Barbie and the teddy bear.

Uncertainty on the Horizon

But all was not well with LEGO leading up to the start of the new millennium. A change of strategy in the late 90s indicated an attempt to rebrand the company in a sense. Instead of sticking to the classic LEGO bricks and sets that had turned the company into a worldwide phenomenon, they began to focus on making toys that were more like action figures. Additionally, LEGO started releasing more complicated sets that did little in the way of allowing creativity from the customer. LEGO also tried out an aggressive strategy of expansion. They built multiple LEGO theme parks throughout the world and even introduced lines of watches and clothing.

Even more distressing was the lack of loyalty company leadership showed to longtime employees. According to LEGO designer Mark Stafford, the company forced numerous designers to retire. These designers had been part of LEGO since the late 70s and had been responsible for some of the company’s best successes. In their place came what Stafford described as “innovators.” They were “the top graduates from the best design colleges around Europe,” Stafford wrote. But he explained the problem:

“Though great designers, they knew little specifically about toy design and less about LEGO building.”

This would all culminate in what was once unthinkable—LEGO would post the first recorded loss in the company’s history in 1998. In total, the loss was more than $27 million in the U.S., which is about $50 million when adjusted for inflation. The loss also came off of a year when LEGO had slashed 10 percent of the company’s workforce.

By 2003, LEGO had accumulated a jaw-dropping $800 million in debt and an additional $300 million in losses. That would increase to $400 million in losses by 2004. The company had gotten complacent with its position in the toy industry, and it was now paying the price. The question wasn’t what LEGO could do to stay on top but whether LEGO could even survive.

The Rebuilding Process Begins

LEGO was in desperate need to turn things around, and quickly. To do so, they would have to break from tradition. The company had been in the hands of the Kristiansen family since its inception, but to introduce change, someone without longstanding ties to the company was brought in to lead. Jorgen Vig Knudstorp became the new CEO in 2005, and when he started, he had his work cut out for him. To put the challenge in perspective, LEGO was losing a million dollars a day.

Knudstorp had experience as a business consultant, but he had never run a company before, let alone one as large as LEGO. He started with LEGO in 2003 as Director of Strategic Development, so he had ideas of what LEGO could do differently, but this would be his first time as CEO. Later recounting his time with LEGO, he said:

“I’ve learned a lot on the fly, and I think, actually, my academic and management consulting background has enabled me to quickly pick up on a lot of disciplines.”

Knudstorp wasted little time enacting his changes, the first being essential cost-cutting measures. He determined that if it wasn’t a core product, it could go. That included selling a majority stake in the LEGO theme parks to Merlin Entertainment, which was part of the investment firm Blackstone Group, though LEGO would still control 30 percent.

More Ownership and Urgency

At the same time, Knudstorp’s transformational leadership installed a new sense of urgency and ownership with employees. Gone was the atmosphere of complacency. The usual product development timeline of two years was shortened to only one year. Now leadership expected LEGO products to be out the door more quickly without sacrificing quality. Knudstorp helped by emphasizing simpler designs, decreasing the number of parts from 12,000 to 6,000.

According to Mark Stafford, Knudstorp brought a sensibility for costs that was absent in the late 90s and early 2000s. Stafford wrote, “The LEGO company at that stage had no idea how much it cost to manufacture the majority of their bricks, they had no idea how much certain sets made. The most shocking finding was about sets that included the LEGO micro-motor and fiber-optic kits—in both cases, it cost LEGO more to source these parts then [sic] the whole set was being sold for—every one of these sets was a massive loss leader and no one actually knew.” As Knudstorp came in, he got rid of this mentality through organizational change.

Partnering With Major Brands

Before the company’s collapse, LEGO had largely stayed away from any tie-ins with major independent properties. Much of what LEGO had done up to that point was purely original, but that would soon change. With the inclusion of a Star Wars line of LEGO sets, the company embraced the idea of tie-ins with intellectual property.

This didn’t start without some controversy, however. Older established employees didn’t like the idea of toys with the word “wars” as part of it, but these voices were in the minority. Star Wars LEGOs would go on to be some of the best-selling sets the company ever produced.

The success of this line of LEGOs would lead to a flood of other popular tie-ins: Harry Potter, Batman, Indiana Jones, Toy Story, The Lord of the Rings, and more. Capitalizing on this movement, LEGO would even have a hit movie in 2014—The LEGO Movie. Not only did it perform well at the box office (over $468 million worldwide), but it also received critical praise.

Connecting With Customers

When Knudstorp became CEO, he felt that LEGO had lost that special connection with its customers. He reasoned that the core customer base wanted to be creative and actually build with LEGOs. They didn’t want to be told what they had to build. As part of his effort to recapture the spirit of LEGO, Knudstorp introduced his “Moments of Truth” to accompany the 10 LEGO characteristics. These moments are questions every employee would need to ask when designing new LEGO sets.

The “Moments of Truth” are summed up as follows:

- Do children want the toy when seeing an advertisement for it?

- Do children want more of the product after opening the box?

- One month later, do kids come back for the toy, rebuild it, and still play with it? Or do they leave it on the shelf?

Additionally, LEGO started recruiting fans to help design new LEGO products. Hardcore fans had a deep love for the company and knew what made LEGOs so much fun to play with. Knudstorp stressed this new level of interaction as essential to the company’s survival. “The Lego children and fans are highly engaged people,” he said, “so they expect a high degree of interaction with us.”

LEGO Climbs Back on Top of the Toy Industry

By 2015, LEGO had not only rebounded from a severe low point, but the company saw unprecedented success. LEGO would call 2015 its “Best Year Ever” with $5.2 billion in revenue. Knudstorp resigned as CEO in 2016, but he remains as Executive Chairman of The LEGO Group. He reinforced the foundation LEGO had created, setting the company up for the future.

The time when the company almost collapsed now feels like a distant memory. Many of the scars from the tumultuous years of 1999 through 2004 have healed. LEGO even struck a deal with a group of investors to purchase Merlin Entertainment, putting LEGO theme parks back in the company’s control. The LEGO Group recently celebrated its 90th Anniversary by opening a newly refurbished LEGO Store in London, which happens to be the biggest one in the world. As long as the company continues to encourage creativity, LEGO will hold to the lessons they’ve learned for many years to come.