Several decades ago, there was one company that was the name in computers: IBM. International Business Machines had earned a reputation for itself by delivering cutting-edge innovations in technology, offering businesses the chance to do things they had never dreamed of before. IBM experienced nearly a century of incredible success, but it also faced a monumental collapse rarely seen in the business world.

The crisis almost cost IBM its very existence, but a series of necessary changes helped the company hold on. A change of leadership would help IBM correct its mistakes, leading to a highly successful rebound. While the company may not be spoken of in the same terms as technological leaders like Apple, Microsoft, and Google, IBM remains an influential entity in technology. That’s thanks to decisive leadership, understanding the company’s roots, and enacting a change in the company culture.

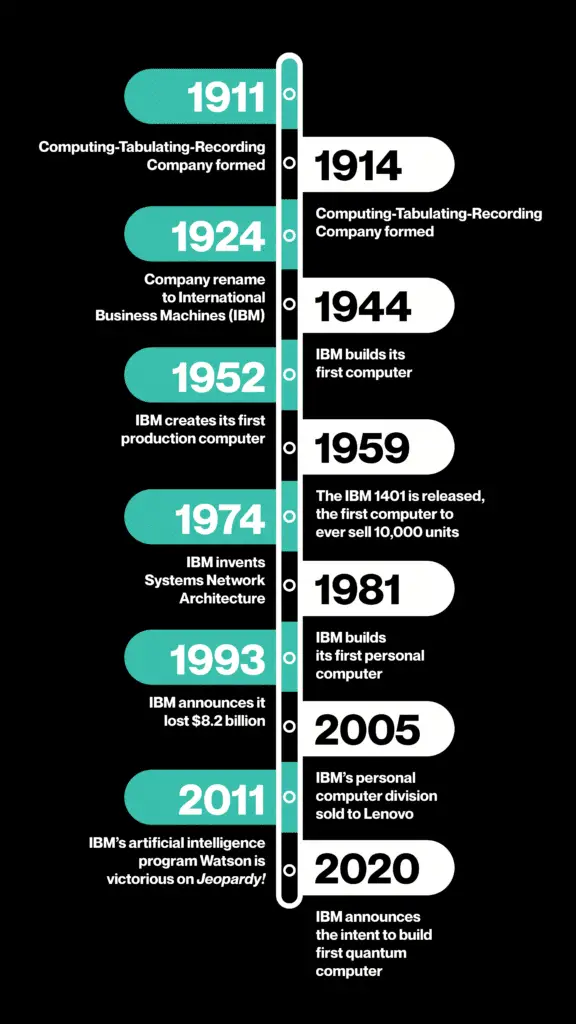

IBM History

The history of IBM begins before computers were even a remote possibility. IBM’s origins stem from four predecessor companies that existed as far back as the 1880s. Those four companies were Tabulating Machine Company (which was the first company to manufacture punch card-based data processing machines), International Time Recording Company, Bundy Manufacturing Company (which was the first company to manufacture time clocks products), and Computing Scale Company of America.

In 1911, those four companies were amalgamated together under a holding company called Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company or CTR, which many people consider the beginning of the IBM timeline. By 1914, Thomas Watson became general manager of the company, eventually becoming president in 1915. CTR’s name would finally change to International Business Machines Corporates in 1924. From there, the company would see sustained growth by creating products like the PA system and the first subtracting calculator.

Becoming One of the First Leaders in the Tech Industry

“It is a common mistake to think of failure as the enemy of success. Failure is a teacher—a harsh one, but the best. Pull your failures to pieces looking for the reason. Put your failure to work for you.”

Thomas Watson

Starting in the mid-1940s, IBM would make a name for itself by developing revolutionary computer technologies. Watson urged the philosophy of constantly pushing new boundaries and experimenting with new ideas. As he once remarked, “Every time we’ve moved ahead in IBM, it was because someone was willing to take a chance, put his head on the block, and try something new.”

IBM would go on to dominate the computer market, eventually making anywhere from 60 to 70 percent of all business computers in the 1970s. The company would try to capitalize on this by launching one of the first personal computers in 1981. While this wasn’t the first personal computer released to the public, having a respected name like IBM launch one lent added credibility to the idea. IBM also developed local area networks for offices all over the world.

In short, the 80s should have been a new launching point for the company, leading to decades of more success. However, by the early 90s, the company was at risk of shutting down.

Failing Against Intense Competition

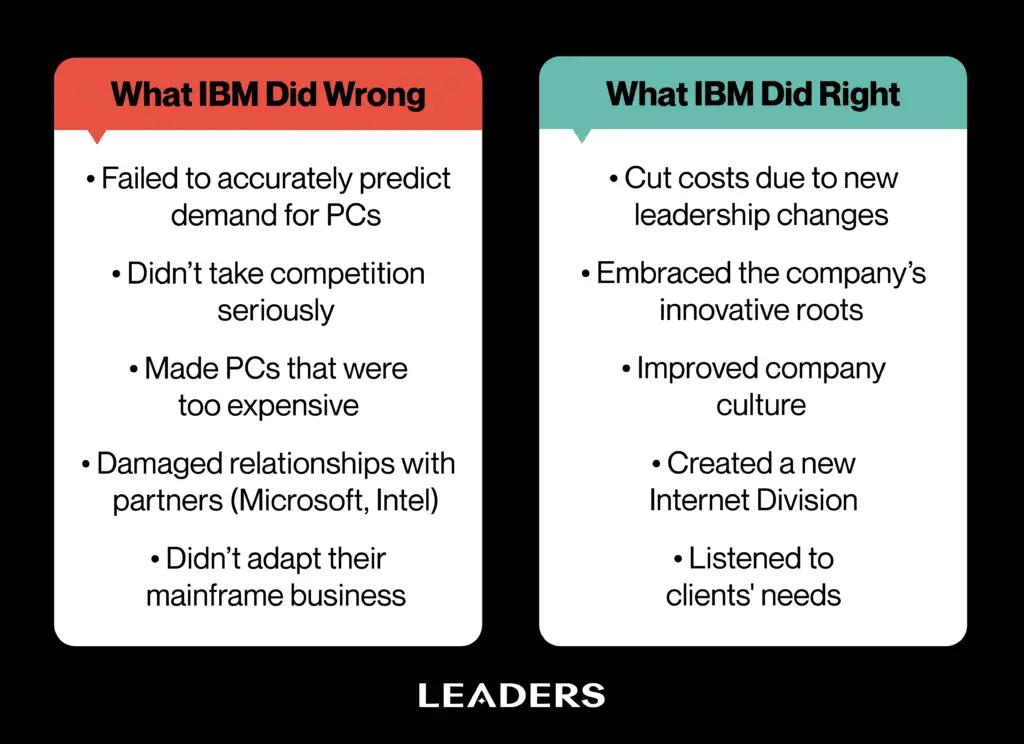

What ever happened to IBM that led to their downfall? IBM’s catastrophe began with their handling of stiff competition in the personal computer market. What should have been a slam dunk for IBM caught them flatfooted.

Personal computers were an emerging market where multiple companies—Apple, Epson, Commodore, and more—were fighting over customers. To be sure, when IBM created their first PC, it was impressive with its 16 KB of RAM, 16-bit CPU, and two floppy drives, but the company failed to properly anticipate how high the demand would be for PCs. That left the door open for clones of its machine to pick up the slack.

More competition meant lower prices, and before long, IBM was no longer dictating the terms of the market. Instead, they were reacting to the changes, always seeming a step or two behind with outdated information.

IBM’s machines were of high quality, but that meant a higher price. Compared to their rivals, IBM’s computers were expensive, and the profits were minimal. As a result of all these factors, IBM’s share of the PC market declined from an impressive 80 percent in 1982 to a distressing 20 percent by 1992.

Problems With Partners

Another advantage IBM had early on was the type of partners they worked with, such as Microsoft. The fledgling software company provided the operating system (MS-DOS) for IBM’s early computers. When it came time to develop a new operating system (OS/2), the two sides had difficulty coming to an agreement on royalties.

Keep in mind this was after Microsoft had already released the first version of Windows. Instead of sticking with that, IBM insisted on new software and ended up continuing OS/2 development on their own. This would end up costing the company up to $125 million per year. Meanwhile, Microsoft allowed other companies to use Windows, which would eventually turn Microsoft into one of the largest businesses in the world. The souring of IBM’s partnership with Microsoft can easily be considered one of the top business mistakes to ever happen.

Another IBM failure happened when IBM failed to gain the proprietary rights to the Intel chip that IBM PCs used. That meant Intel could sell its chips to other companies.

Tragedy Strikes at the Top

One thing outside of IBM’s control was a tragedy that would profoundly affect the company for many years. In 1985, Don Estridge and his wife Mary Ann died when Delta Flight 191 crashed at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. Of the 162 people on board, 131 died. The accident shook IBM to its core. Estridge had been the main mind behind the development of the IBM PC. He had risen through the ranks and become IBM’s Vice President of Manufacturing.

According to the New York Times, Estridge was considered a pioneer in the field of personal computers. He had a strong, optimistic vision of what computers could become and what IBM could provide to the world. Without his confident leadership, IBM had difficulty navigating the tricky waters of the competitive PC marketplace. There’s no way to know how he would have handled the challenges the company faced, but it’s likely he would have been a powerful voice in innovation and creative solutions.

Summary

A failure to capitalize on its unique position in the market, souring relationships with business partners, and a tragic leadership loss all contributed toward IBM’s decline.

The “Near-Death Experience”

By the time 1993 rolled around, IBM was in rough shape. The company announced that for the 1992 financial year, they had lost $8.2 billion. To put that in perspective, that amount at the time was more than any U.S. company had lost—ever. Forbes contributor Steve Denning referred to this as IBM’s “near-death experience.” Not only had IBM lost ground in the personal computer market, but that market had also caused a disruption in their lucrative mainframe business.

In a sense, IBM’s immense size, while valuable, was also one of its biggest drawbacks. In a world where agility was paying off, IBM had transformed into a lumbering behemoth. They found themselves unable to compete and constantly losing ground. If the company was to survive, it would have to make significant changes.

A New CEO Shakes Things Up

When IBM brought Louis Gerstner on board as CEO in 1993, it seemed an unorthodox choice. This was the first time IBM had selected someone outside the company to become CEO in its history. On top of that, Gerstner had no experience working for a computing company. His prior leadership stints were at American Express and Nabisco. While it may have sounded like he was unsuited to head up a technology company, his leadership proved to be a difference maker.

Gerstner first sought to bring down the costs the company was racking up. In Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?: Inside IBM’s Historic Turnaround, Gerstner explained the importance of having a long-term plan in place, stating:

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

He knew costs were a major problem and sought to drive them down by freezing long-term projects. Some measures he enacted were painful, such as laying off 35,000 employees. Yet, with how large the company had gotten, these policies were likely necessary to keep the business profitable.

Returning to the Company’s Roots

Gerstner also had a specific goal in mind for the company. “I want to take IBM back to its roots,” he said. That meant returning IBM to a B2B company. From his previous experience, he knew businesses still needed to work with a company that could integrate their technological solutions.

Leading the charge was the newly formed IBM Internet Division, a part of the company aiming to promote an internet strategy to clients. The task of convincing clients that the future was in network computing through the internet wasn’t easy. To advance this vision, IBM’s marketing team coined the term “e-business,” and the name soon stuck. By selling the value of the internet, IBM stood at the forefront of offering cutting-edge solutions once again.

Cultural Changes at IBM

“I came to see, in my time at IBM, that culture isn’t just one aspect of the game—it is the game.”

Louis Gerstner

When Gerstner became CEO, IBM was suffering from what Eric Flamholtz the President of Management Systems Consulting calls “corporate arrogance.” There was a general belief that IBM was a company that could do no wrong—no matter what happened they would be all right.

This attitude masked the real problems IBM was facing. Gerstner wrote that changing the culture was the real challenge he needed to solve. “Yet the hardest part of these decisions was neither the technological nor economic transformations required,” he wrote. “It was changing the culture—the mindset and instincts of hundreds of thousands of people who had grown up in an undeniably successful company, but one that had for decades been immune to normal competitive and economic forces. The challenge was making that workforce live, compete, and win in the real world.”

Gerstner led the charge in changing IBM’s culture. He returned to IBM’s roots once again by emphasizing Thomas Watson’s organizational culture of innovative thinking. IBM would later adopt several pillars to help define the culture. These guiding principles include:

- Dedication to every client’s success

- Innovation that matters, for our company and for the world

- Trust and personal responsibility in all relationships

A New Golden Age

Gerstner’s leadership got results quickly. By 1994, about a year after he joined the organization, the company reported $392 million in profits along with an increase in revenue. The stock price, which had hit a low point of $10 per share in 1993, would go on to hit $123 per share by 1999 and now sits at around $133 per share.

Gerstner would eventually retire in 2002, but during his tenure, IBM’s business grew from $64 billion to $88 billion. Even more impressive, analysts say he took the company’s market capitalization from only $29 billion to an astounding $168 billion. As Gerstner put it, “The vast new challenges of networked computing reenergized IBM research and triggered a new golden age of technical achievement for the company.”

Can IBM Sustain Success?

IBM continues to develop new technologies, such as with artificial intelligence and machine learning. They also continue to focus these technologies on the business side, with IBM’s Watson used as an artificial intelligence product for companies. Even after all sorts of changes, IBM is still one of the global leaders in computer and system integration.

While IBM was able to turn around its fortunes, that doesn’t mean the company is out of the woods. Issues such as supply chain integration and a lack of progress in its cloud computing division have shown that IBM still has significant challenges to deal with. At the same time, a series of scandals indicate the company needs further reforms if they want to continue improving the culture through greater transparency and accountability.

No company can guarantee success. If IBM wants to stay alive, it will need to address these challenges through improvements to its leadership team. The problem may not be related to product but rather personnel. The last thing the company needs is for corporate arrogance to creep back in. IBM may have experienced an incredible rebound in the 90s, but the company must take the lessons it learned from that time and apply them today. If not, they may suffer a fate they seemingly avoided decades ago.

To learn more about effective leadership, check out these articles:

Leadership Requires These Qualities of a Person

What Does It Mean to Be a Leader?

How to Build a Business Culture as an Executive Leader

Leaders Media has established sourcing guidelines and relies on relevant, and credible sources for the data, facts, and expert insights and analysis we reference. You can learn more about our mission, ethics, and how we cite sources in our editorial policy.

- Reed, E. (2020, February 24). History of IBM: Timeline and Facts. TheStreet. https://www.thestreet.com/personal-finance/history-of-ibm

- Personal Computer History: 1975-1984 | Low End Mac. (2023). https://lowendmac.com/2014/personal-computer-history-the-first-25-years/

- Cortada, J. W. (2022, August 30). How the IBM PC Won, Then Lost, the Personal Computer Market. IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/how-the-ibm-pc-won-then-lost-the-personal-computer-market

- Markoff, J. (1992, June 28). I.B.M. and Microsoft Settle Operating-System Feud. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/28/us/ibm-and-microsoft-settle-operating-system-feud.html

- Alsin, A. (2020, July 29). The IBM Hall of Shame: A (Semi) Complete List of Bribes, Blunders and Fraud. Medium. https://medium.com/worm-capital/the-ibm-hall-of-shame-a-semi-complete-list-of-bribes-blunders-and-fraud-19e674a5b986

- Cornwell, R. (1993, July 31). Profile: The iconoclast at IBM: Lou Gerstner enacted unprecedented. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/profile-the-iconoclast-at-ibm-lou-gerstner-enacted-unprecedented-cuts-at-the-giant-computer-firm-last-week-but-he-will-need-to-do-more-than-wield-the-axe-to-revive-it-rupert-cornwell-reports-1458529.html

- Denning, S. (2011, July 10). Why Did IBM Survive? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/07/10/why-did-ibm-survive/?sh=343ff9421cac

- Flamholtz, E. (n.d.). The Dark Side of Corporate Culture: The Metamorphosis of Culture at IBM. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/dark-side-corporate-culture-metamorphosis-ibm-eric-flamholtz/

- IBM Historical Stock Lookup | IBM Corporation. (n.d.). IBM Corporation. https://ibm.gcs-web.com/stock-information/historic-stock-lookup/?auth_token=5e5458b8-954c-409b-96fc-97b4be809bd6

- Krazit, T. (2021, October 14). How IBM lost the cloud. Protocol. https://www.protocol.com/enterprise/ibm-lost-public-cloud

- Libert, B. (n.d.). The Network Imperative. O’Reilly Online Learning. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/the-network-imperative/9781633692060/Text/chapter006.html

- Our Approach. (n.d.). Our Approach. https://www.ibm.com/ibm/responsibility/2015/at_a_glance/our_approach.html

- Parziale, E. (1985, August 4). Personal Computer Developer Among Dead In Delta Crash. AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/article/083db2134e6d97743084f364bd762362

- Sanger, D. E. (1985, August 5). PHILIP ESTRIDGE DIES IN JET CRASH; GUIDED IBM PERSONAL COMPUTER. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/08/05/us/philip-estridge-dies-in-jet-crash-guided-ibm-personal-computer.html

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2023, February 25). Lou Gerstner | Biography, IBM, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lou-Gerstner